(excerpted from my 2017 book “Life on the Ground Floor”)

I’ve been cutting down my shifts in the last few years so I can spend more time on Ethiopia. I work about ten a month now. It’s just enough to keep my skills up. Fewer, and my fingers fumble.

When I graduated, I did twice as many. During those months, being in the ER was simpler than it has been since. My flow was natural, my hands steady, and my patients’ faces grew as indistinct as the date or time. It was the hours outside of work that started to hurt. It is easy to ignore your own worries when there is a never-ending list of worse ones placed in front of you. My relationship failed. Friends fell away. Beauty too. I felt fine.

I wasn’t. Fatigue caught up with me and I slowed down for a minute, looked around, wondered where everyone was.

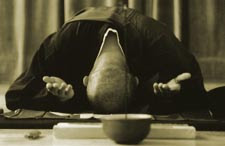

If we in ER gather in community, it is to talk about how to resuscitate a baby, to poke needles into fake plastic necks, or to practise for poison-gas subway attacks. We don’t practise joy, how to stay well in the face of all the sickness.

Doctor, Nurse, heal thyself.

Or not. Those who work in the ER burn out faster than any other type of physician. I’m not sure if it’s the shifts or the long, steady glimpse of humans on their worst day.

I think most of us would say that it’s not the sickest that affect us, that it is the minutes in contact with them when we feel most well used. In a macabre way, we hope for the next person to have something really wrong with them, but it is more rare than you’d imagine to see a critical patient in Toronto, even in the trauma room, someone whose system needs the order the alphabet can bring.

Most of the work here is in minor. ERs are open all hours, and since the service is free, people often come in early, instead of an hour too late. Sometimes there is nothing wrong with their bodies at all. There are so many measures in place to keep people well, or to catch them before they get too sick, I can go weeks without intubating someone. Worried minds, though, latch onto subtle sensations that magnify with attention, and lacking context, they line up to be reassured. The two populations, the sick and the worried, mix together, and separating them keeps us up all night.

Suffering souls, though, there is no shortage of them. They circle this place.

Some sleep right outside, on sidewalk grates, wrapped in blankets, waiting. One is splayed in the clothes he lives in, face pressed against the metal grille in a deep, drunk sleep. Every few minutes, a subway passes below the grates, and a rush of warm air flutters his shirt like a flag.

Businesswomen spin in and out of an office tower’s revolving doors. They cross the street, eyes dancing between their phones and streetcar ruts, pretending not to notice the figure on the ground. Shoppers with bags from the Eaton Centre dangling from their arms lean into the road looking for taxis, jump out of the way of rushing cars.

A guy across the street notices the body. He glances at it, then at the hospital, makes a calculation that there must be no better street grate in the city, and moves on. Others step over him, as if he was downtown city furniture.

Within a few blocks of my ER, there are a dozen shelters for abused women and the homeless. There are health clinics for indigenous people, gay men and women, refugees, detox centres, beds for kids who’ve run away from home. On my way to work I pass them, pierced, dyed, smoking. Sometimes I’ll see them in the ER, shyly pulling away a bandage from the cuts they made on their arms.

Seaton House, a men’s shelter just up the street, holds more than five hundred. It has an infirmary for the old and the sick, a special floor where the most craven alcoholics are given brandy every hour, so they don’t die on those grates. A patient told me that the floors are patrolled by gangs, and if you’ve a bag, they will pin your arms from behind and rifle through it, taking what pills or dollars there are.

“They call it Satan House.”

He was new to Toronto, to big cities even. He sat on our bed, his bag empty and eyes wide.

“I can’t go back there. Drugs. Bugs. Fights. Can I stay here? Just one night?”

Sorry, man. Here’s a list of other shelters, a central access number, a sandwich, a prescription for the medicines you lost, a number for our social worker who can help you fill it, a bus token, a bandage for your foot. But I’m sorry, this ain’t no hotel.

He held his backpack tight, under the sheets, shook his head, no fucking way. Security hoisted him from the bed, a guard on each arm, walked him down the hallway, out the door, into the night.

We give out clean needles, single-use vitamin C sachets so people can dissolve crack or black tar heroin in its acid instead of sharing lemon juice and scarring their veins. Some people come in just for sandwiches, or to use the phone. Others, to sit in a chair.

One of my colleagues rolled a man in a wheelchair out into a storm. The man had been pretending he couldn’t walk, but when Jeff’s back was turned, he would stand, grab hand sanitizer from the wall, and drink it down. He’d been doing it for hours before someone noticed. After Jeff pushed the man out, he sat back down at the desk in minor, began angrily filling out the man’s chart, paused, then slammed his pen down and, furious, snowflakes melting on his scrubs, wheeled the man back in. Our trust gets broken and broken and broken and broken, but underneath it is an even deeper caring.

A few years ago, I heard an overhead page—“Dr. Maskalyk to triage”—and I walked out, to help decide which way to direct a stretcher I’d guessed, and instead saw a bailiff who touched me with an affidavit, dropped it, furled, on the ground.

“Sorry,” the registration clerk said to me, bashfully. “I thought he was a friend.”

I picked up the rolled paper. A lawsuit. It named many doctors. I couldn’t remember the complainant.

I got his chart from medical records. It didn’t cue me. I’d met him once, two years before. I could remember the night. So busy, running from minor to major every few minutes. I have a vague memory of his back, but not his face.

The chart was mostly empty. “Flank pain” was his complaint, and I scratched in only a few physical findings. In the margin was a note from the nurse: “Verbal order, Maskalyk, morphine 5 mg IV.” You get calls like that all the time, from a worried nurse, asking for pain relief for someone writhing in a stretcher. Sure, sure, I would have said, after I asked a few questions, 5 milligrams.

In the years that had passed, I had touched a hundred backs, seen many people in pain. This man was fine. There was no bad outcome. He had CT scans, MRIs, all negative. His charge to me was that I contributed to his opiate addiction. He named every doctor who had crossed his path.

The case dragged on for years. My lawyers kept telling me that it would go no further, but it kept limping. Every few months, another letter, until whoever was helping that man exhausted what money he had and the case was dropped.

Some of my colleagues haven’t been so lucky. Sometimes that person with back pain that sounded the same as the hundred before in fact has a hemorrhage, or an infection, and becomes paralyzed. I received an angry letter from a family doctor who said I was incompetent for not x-raying the leg of a young woman he had sent to the ER. She hadn’t fallen, hadn’t endured an injury. I examined her leg. No swelling, no chance of a break. Not blue, good pulse. No emergency as far as I could tell. Does it hurt when you do this? Stop doing that, I said, every doctor’s favourite piece of advice. Rest it, see if it gets better. It didn’t. The bone had a tumour in it.

Shoulder pain in a drunk man, sleeping it off in the hallway. This time, I got an x-ray. Negative. The pain persisted. I CAT-scanned his neck. Broken. The pain was from a pinched nerve. He hadn’t complained of neck pain, couldn’t remember falling. But I didn’t feel along his neck until much later. I should have. I didn’t even put a collar on before I sent him to scan. A screaming radiologist called me in minor. “What the hell are you doing sending him up alone?”

First shift, after I graduated. A pharmacy student with severe asthma. Often, patients with chronic disease know what they need. Adrenalin, intramuscular, he said, requesting our most powerful drug. I found a nurse, told her what I wanted, stepped away to write on his chart, turned back to see the colour drain from her face, watched him fall back onto the bed. How did you give that adrenalin? I shouted, my finger already on his neck. Intravenous, she said, knowing her mistake, that in a living person, it must never go straight into the blood, that it is too much for a beating heart to take.

Shit, I said, lacing my fingers together before hammering down on his chest.

He lived. I told him what had happened, then my chief and the nursing supervisor. The patient understood, probably better than anyone in the world. At least my asthma’s gone, he said, wincing as he tried to sit up.

I could go on. No matter how careful I try to be, I make mistakes. The next one is just waiting.

We are taught all kinds of things as we work our way down the alphabet. To spot a hurt person, to remain suspicious, to learn from our errors. It can be difficult to rest from the worry.

“You will fucking too see this patient,” I said to a resident who refused to assess a woman with AIDS who couldn’t stop vomiting long enough to take her pills and had nowhere to go. “Because it’s your fucking job, that’s why.” Anger shook me.

“You stupid jew cunt!” a patient yells at my colleague.

“Handshandshands!” a security guard shouts as the man they are watching undress pulls a knife.

“I have hep C, and if any of you come close, I’ll spit in your eye!” another man, scratched and bruised, screams, five cops holding him down. He was released from prison a day before, having served twenty for murder. In his hours of freedom, he beat another man nearly to death. “Come here,” he says, looking at a nurse behind me. “I dare you.”

I’ll sue you. I’ll stab you. I’ll come back with a gun and kill all of you. You’re a shitty doctor. You’re an ugly nurse. You’re an idiot. Goof. I want a second opinion. I want to kill myself.

Dying person, dead person. Sick person. Lying person. Faking. Manipulative. Poisoned. Raped. Dead. Screaming. Crying. Writhing in pain. Hopeless. Afraid. Confused. Alone.

Wow, must be stressful, people say.

You get used to it, we answer.

Ground floor, downtown, ground down. Suffering can be contagious, and no matter the job you do, it just keeps coming back.

Your world view skews. If you don’t make an effort to balance it, the ER becomes your new normal. Like a home, you turn to it for what you need. Your colleagues seem like the normal ones, because they can joke while a man, shot dead, lies behind them.

Daddy, a colleague’s daughter said, all you do is work, sleep, and drink. A nurse told me after a string of five days in a row, she took a bottle of wine to bed, and cried.

It’s hard to make it ten years here. Some don’t make it two. It’s worse for the nurses. They spend more time at the bedside, unobserved, unprotected. They watch people die over hours, asking, “Am I going to make it?” again and again. I get asked once. “We’ll do what we can,” I say, and move on.

The ones that last are changed. The shifts, the swearing, the shouts of pain, the anxiety and sadness and anger pouring from strangers. Miss a decimal place and someone’s dead. Drug seekers lie to your face so they can flip pills on the street, and you grow suspicious of those in real pain. The addicts and alcoholics who circle this place, lost and dying, whom you can’t help and no one else wants. A security guard had his nose broken one week. A nurse, a chunk of hair ripped from her head. She waited until it stopped bleeding, then finished her shift. I haven’t seen her since.

We work when we are sick, masks over our faces so we’re not contagious. I broke my arm, and didn’t miss a day. We have a silent agreement to not ask for help. Sickness becomes weakness, weakness a sickness.

It’s rare to connect with the people I treat. The ones I do best for wake up in the ICU, in a sedative haze, not sure what happened or whom to thank. We deliver more dead babies than live ones. No one shouts, “Mazel tov! It’s appendicitis!”

We don’t develop relationships with patients, claim that we prefer it that way. We dive deep, straight, unapologetically, unsentimentally, into a person’s worst fears, ask them about sex, drugs, who’s hurting them, why they’re hurting themselves. We look in their eyes, watch them cry, put needles into their veins until they’re plump with water, dab blood from their cervixes, know their bodies more intimately than they ever will. When the new shift comes in, we go home and try to live in ours.

I sat in my first suit, tugging at the cuffs, and told the doctors across the table, ones who were deciding whether they would let me into their emergency training program, that I thrived on the type of challenges the ER presented. I didn’t mind odd hours and had healthy habits to make up for tough nights. They nodded, satisfied, and I walked out, past a half-dozen nervous young men and women, their answers the same as mine.

We get ground down anyhow. The pace, we’ll say, images of mangled limbs we take with us wherever we go. It’s hard to leave, even if you know you should. It feels good to be surrounded by those who know what you do, to whom you don’t have to explain.

Some of us make it through. Some drink. Some smoke. The ones who last best, laugh. Even about the black things. Especially about the black things. Without the absurd, there is only tragedy.

A woman, twenty, fell down twenty stairs. One eye was swollen shut. She wouldn’t answer to her name or open her other eye. She pushed at the nurse’s hands that tried to help her, again and again, sought to climb out of bed. I sedated her until she was still, and did a CAT scan of her brain. The scan showed bruising, blood in the grey matter where there should be none, a slick of it pooling inside her skull, squeezing her brain tighter and tighter. I called the neurosurgeon, a German, and explained what I saw.

“So she needs the OR,” I said over the phone.

“Is she . . . pretty?” he said in a heavy accent, chewing, swallowing.

“I don’t know . . . I guess so.”

“Zen we must to do everysing,” he said, and hung up the phone.

A few hours later, nurses and I recalled the conversation as we switched back and forth for CPR. We laughed, above an old woman’s still heart, caught ourselves, turned our eyes back to our work, and fell into smiles.

You can see those who are edging out. When we’re unable to meet the sadness, or to laugh about it, cynicism takes hold. Even worse, anger. We curse nurses on other floors for being too slow. We criticize our colleagues’ decisions, their flow, their bad day, forgetting that they, like us, are just trying to make it through a shift, a week, a month, a life, surrounded by all the pain.

Last, we curse our patients. This is a final sign. Touching many people, but being touched by none of them, they close like a flower that no longer sees the sun. It’s as if every person takes away from you something you need.

Not her again, a nurse says under his breath, as a volunteer places a chart of a regular on the desk, as if this wasn’t the point of the place, as if this didn’t happen twenty times a day.

People think that to make it through, we become inured, develop some kind of barrier, beyond emotion. It doesn’t work like that. You can offer an illusion of indifference, even tell yourself that you’ve got it handled, but all that tough stuff makes it in just the same. What shuts down is the part that turns it around.

There’s too much to do, a next patient to see, and if you’re never told how important it is to work on anger and fear as it comes up, you put it off, and the frustration diffuses into all aspects of your being, its origins almost invisible. You can get so behind, you abandon the project. Then, on that fateful day, when you have a chance to do something right for someone you don’t know, or cut a corner, you say to yourself, “Fuck it.”

The end has come. Time to quit.

People do. Plenty. I’ll see them in the hall after many months, when I used to see them every day. Miss us? I’ll ask. Yeah, they say, I do, some of them wistful. But I just couldn’t do it anymore. It wasn’t good for me.

What they mean is, instead of just the worries following them home, some numbness did too. Joy started to seem for fools, because while there are many things we will never know, what we do know for certain is that one day, a bullet meant for someone else will whip through our body, our foot will turn on a dog’s toy on the second stair and we will fall, or a cough will tickle our chest then sputter a tablespoon of blood, and in an instant we know what it means.

It’s here.